No passing bells. . .

Hazel Basford, the KCACR Librarian, has been doing a lot of research into the lives and deaths of KCACR ringers during the First World War.

NEW 11 November 2000: There is some recently acquired information about the ringers of Dover.

NEW 13 March 2001: A new name, Charles Colbreay, has been added to Charing.

NEW 30 December 2001: New names, Clarence Smith (Boughton) and Edgar Coachworth (Hernhill), have been added.

NEW early 2002: New information on Charles Colbreay, George Mills and Tom Cox.

NEW November 2002: News of the Hayesmore brothers.

NEW 4 December 2010: New name, Fred Rayfield of Hartlip.

NEW 20 June 2013: New information, William Barton Young of Christ Church, Erith.

At the end of June 1996 on a hillside at the edge of a village near Albert in France we walked along the rows of identical white headstones set in borders of flowers of home. We scanned the names looking for the one we sought — William Audsley. Eventually we found him, high up the slope. We read at the top of the stone “414653 Gunner W T Audsley, Royal Field Artillery 9 February 1917 Age 20”. At the bottom of the stone, part hidden by the foliage was an inscription chosen by his family “Never forgotten in Crayford”. Yes, this was the one.

By 1914 The Kent County Association of Change Ringers, which had been established in 1880, had over 1,200 members. The Annual Report spoke of satisfaction with the achievements of the first 34 years of the Association’s history “we are gradually drawing towards the day, when . . . change ringing shall be firmly established in all our county towers, and good ringing . . . “. 153 peals had been rung in the preceding year, involving 44 conductors and a quarter of the membership. Yet in 1914 everything changed dramatically. The Great European War broke out, ringing was soon severely curtailed, and life was never the same again.

At the outbreak of war many ringers joined up, altogether nearly 500 Kent ringers saw service in the Armed Forces. The Ringing World began to publish lists and news of serving ringers, including letters from the front. Several recount how, if they had free time, the men would check out the bells of the nearest church, perhaps chiming them to remind them of home. All too soon, of course, came news of casualties.

In early 1917 the Kent Association was one of the first “to consider the question of providing a suitable memorial to those members who had given their lives for King and Country”. The Lewisham District proposed the addition of two treble bells to the ring at Canterbury Cathedral to make the peal up to twelve and this was accepted. The decision had greater significance in that no church tower in the Association’s area had twelve bells at that time. The bells were finally dedicated by His Grace The Archbishop following Evensong on Saturday 13 October 1923. In his address His Grace said of the bells “When they sound out over our old City and the hills which encircle it, the familiar message will now be enriched by new thoughts and new associations as we recall the brave men, some 56 in number, who belonging to our Association, ringers in our Kentish parishes, gave their lives.”

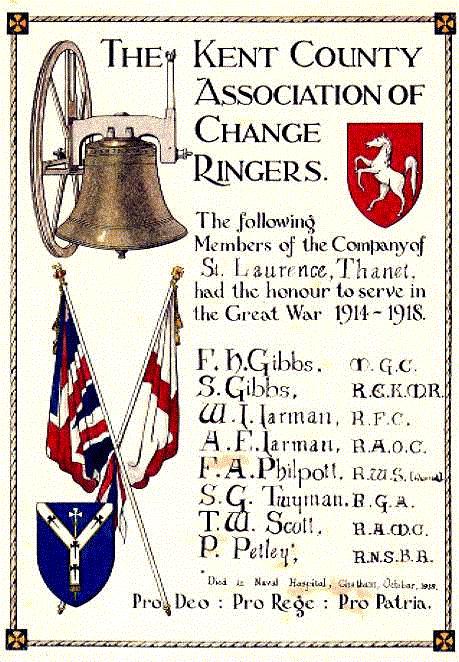

The total cost was £249 2s. 3d. which was almost equal to the sum raised. It had been proposed to erect a tablet under the tower giving the names of the ringers who had died but this seems to have proved impossible and thus today unfortunately very few people know of the memorial. Ringers visiting the tower may notice a framed reference to the opening of the bells and the Association certificate made available after the War for towers to record the service of their ringers. The bells, which were recast in 1981, of course still carry the memorial inscriptions on two treble bells.

A couple of years ago I thought it would be interesting to gather a list of the members who had served, as well as those who had died. My principal source was the Annual Reports, which during the war period listed service members and later, casualties. I also read wartime editions of The Ringing World and found some men whose names had been omitted – the General Secretary regularly reminded members to send him details but some were obviously not forthcoming. I may have included a few who were not actually members but as service members did not pay a subscription this became rather a grey area during the war and my criterion has been “a ringer from Kent”. Among my list of 81 men from 51 towers are several whose names were recorded on belfry Certificates but not in the Reports and others, such as William Coveney from Ospringe, who while not serving in the armed forces was engaged on munitions work when he was killed in an accident at the Cotton Powder Works at Faversham. His name is on the war memorial at Ospringe and on the certificate in the tower. The greatest loss was suffered by Chiddingstone where five of the band died.

Looking at the names as I gathered them I became curious as to what had happened to the ringers and where they had died. Having visited the Western Front in the past, I wondered if any were buried or commemorated just across the Channel, almost within sight of home. Happily I have been able to track down all but a couple of the men (to date). The majority are, unsurprisingly, on the Western Front but others are in India, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Israel, Greece, Italy and Gallipoli. A few are buried at home, having died from illness or as a result of injury. My sources have been the usual ones – the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the indexes at the General Registry Office and “Soldiers Died in the Great War” (recently released on CD-ROM and so now fully searchable). In about ten cases I have had contact with families of the men and have been given photographs. In an extraordinary coincidence I found information on the circumstances of the death of two of the ringers in Lyn Macdonald’s book The Roses of No Man’s Land. Both died when ships were sunk. An examination of war diaries at the Public Record Office has provided more information about the whereabouts of the men when they died and what actions they were involved in at the time.

Together with Hedley, my husband, and ringing friends Jack and Freddie Peppiatt, I have now made several trips and visited most of the graves or memorials to the Kent ringers in France and Belgium. Twenty nine are on memorials to the missing, a percentage which I still find quite shocking. Wherever we have visited we have played a tape of the Canterbury bells as a tribute. Our English bells were a sound these men loved and is never otherwise likely to be heard across these “foreign fields”.

Hazel playing her tape of Canterbury Cathedral bells at the grave of William Audsley

To tell the story of all the men would take too long and in any case some I know very little about — yet. The quest will no doubt continue. However to choose just three:

The first ringer to lose his life in the conflict was Percy Gibbs who was elected a member on 2 April 1913, prior to a peal of Grandsire Triples at Dover. During the rest of his time in Kent he took part in another six peals, including ones at St Stephen’s, Canterbury, and Gillingham. Percy Gibbs was a regular soldier with The King’s Own (Royal Lancaster Regiment) and must have been stationed at Dover as he seems to have joined the band there. He was born in Worcestershire and must have been a capable ringer by the time he came to Kent but I have been unable to trace his earlier ringing career. War was declared on 4 August and that evening Percy Gibbs’s battalion received mobilisation orders. They travelled to Norfolk and later North London for training and embarked from Southampton as part of the British Expeditionary Force on 22 August. They travelled by train to Bertry, a small village east of Cambrai, arriving on 24 August when they were ordered to take up defensive positions in the face of the advancing German army. The next day they suffered shell fire but without casualties. However the following morning, while moving to a new position near the village of Haucourt, they were caught out in the open by the withering fire of Maxim guns. 58 men of the Battalion were killed that day, including Percy Gibbs. The BEF continued to fall back before the onslaught until the German Army was stopped several weeks later at the Marne river some sixty miles to the south. Percy Gibbs has no grave; he is commemorated on a memorial to the 4000 missing soldiers of the early weeks of the war at La Ferte-sous-Jouarre.

The most decorated ringer of the war who lost his life was George Skeer of Brabourne. He was a Serjeant with the 222nd Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery and he died of wounds on 21 March 1918. For his bravery George Skeer was awarded the Military Medal and the Belgian Croix de Guerre. His son Donald Skeer, who died recently, wrote to me about his father. He remembered as a very young boy “fetching the post from the postman and taking it upstairs to my parents who were still in bed and my father opening this important looking letter which might have been a recall from leave, instead it was notification of award (of the Croix de Guerre)”.

George Skeer

George Skeer came from a family of soldiers. He served in the RGA from 1900 to 1908, when he left the Army to become Brabourne’s postman. It must have been at this time that he learnt to ring at Brabourne church where he was also a sidesman. He volunteered for active service when war broke out, was sent to Flanders in June 1915 and was wounded in August while serving with a trench mortar battery at Hooge. After a period on home defence at Portsmouth, he went back to Flanders in February 1917. 21 March 1918 was the day the German army launched the Kaiserschlacht — the ‘Kaiser’s Battle’ with a massive artillery bombardment on the British front in France. George Skeer was apparently not on duty that day but was voluntarily assisting to move the guns of his battery in the face of the enemy advance. Unfortunately the battery’s war diary is lost so its position is unclear but it seems to have been with the Fifth Army which took much of the brunt of the attack and lost 383 guns that day. George Skeer is commemorated on the memorial to the missing of the Fifth Army outside the village of Pozieres on the Somme.

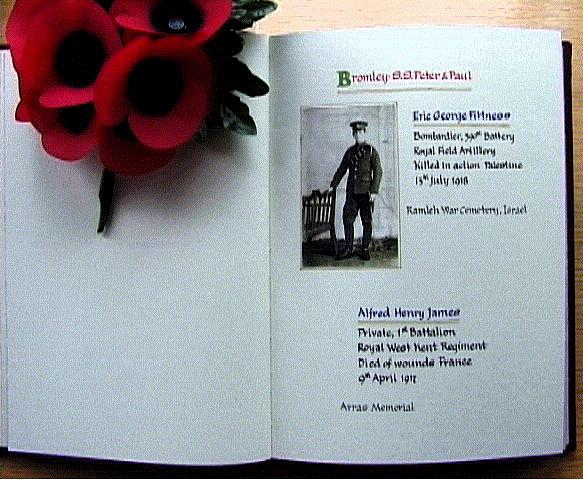

Perhaps the greatest loss to the Exercise in Kent was Eric Filtness of Bromley. He was a Bombardier with the Royal Field Artillery. The Ringing World reported his death in July of 1918, aged 23, at a forward post in Palestine. He is buried in Ramleh War Cemetery not far from Ben Gurion Airport in Israel. The report commented that he started to learn “at the age of 16, he made rapid progress, and before he was 19 was composing and conducting touches of Stedman and Double Norwich from any bell, and conducted a peal of Bob Major just about his 19th birthday.” His daughter, who never knew her father, lives at Bickley.

One of the most interesting items I received through contact with families has been the photograph of the original grave marker on the grave of Merrick R Warnett of Lewisham who died aged 25. His father, Harry Warnett, tower captain at Lewisham for many years, was listed as an Association “Instructor” as early as 1891and his brother was also a ringer. Merrick joined up in August 1914 and saw a lot of action, including Loos in September 1915. He suffered a fatal wound in May 1918 and is buried at Contay, Somme in a burial ground used by one of the Casualty Clearing Stations. As a service to grieving relatives the War Graves Commission photographed graves after the war and made them available, together with full details of the location, including the nearest railway station.

Merrick Warnett’s grave marker at Contay

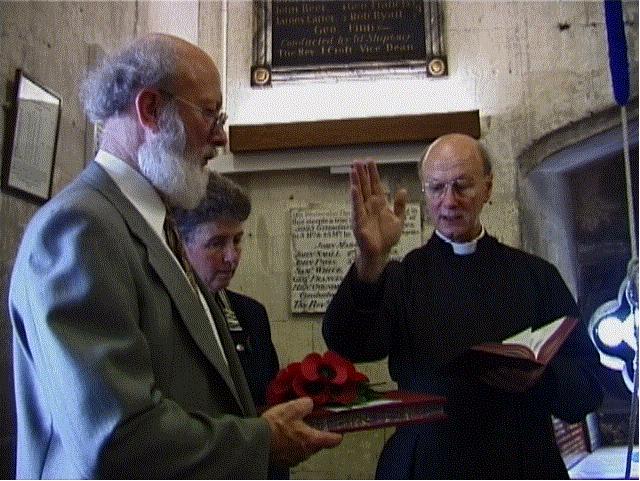

On Sunday 20 June 2000, in the belfry of Canterbury Cathedral, Canon Peter Brett received the Roll of Honour on behalf of the Cathedral and handed it into the safekeeping of the Cathedral ringers. He spoke of the long tradition of writing names in books, before blessing the Roll of Honour and offering prayers for those who are named within it. Relatives of two of the men named were present which made the occasion very special for those attending. Ringers from Linton and Queenborough came as well as Association Chairman, Frank Lewis, on his first official duty and Secretary Tim Wraight.

The dedication of the Roll of Honour (Frank Lewis, Hazel Basford, Peter Brett)

For me personally this was the closing moment of a journey I will never forget. The names of the 81 Kent ringers who died during the First World War will always be familiar to me as will the memorials and cemeteries at which they are honoured and remembered by their Country. Our Roll of Honour will I hope become a treasured reminder to ringers both of the men themselves and of our loss in their passing.

A page from the Roll of Honour

Have you forgotten yet?

For the world’s events have rumbled on since those gagged days,

Like traffic checked while at the crossing of city-ways:

And the haunted gap in your mind has filled with thoughts that flow

Like clouds in the lit heaven of life; and you’re a man reprieved to go,

Taking your peaceful share of Time, with joy to spare.

But the past is just the same — and War’s a bloody game . . .

Have you forgotten yet? . . .

Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.

From Aftermath by Siegfried Sassoon.

Hazel Basford, Hon Librarian, November 1998 (updated November 2000)